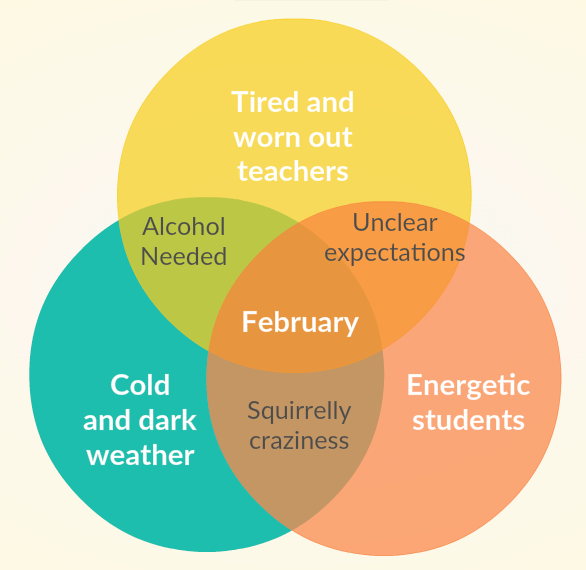

February is has always been a difficult month for me. It always has been, and I predict it always will be (at least in the current system as a teacher). It is cold; it is dark; it is that perfect sweet spot where the beginning-of-the-year expectations have seemed to be forgotten, energy is drained, and the end of the school year is too far away to smell hints of its sweet release.

Although, I probably could write about the coping strategies needed to get through these difficult weeks, I’d prefer to share something I’ve been thinking about in regards to classroom expectations during this time.

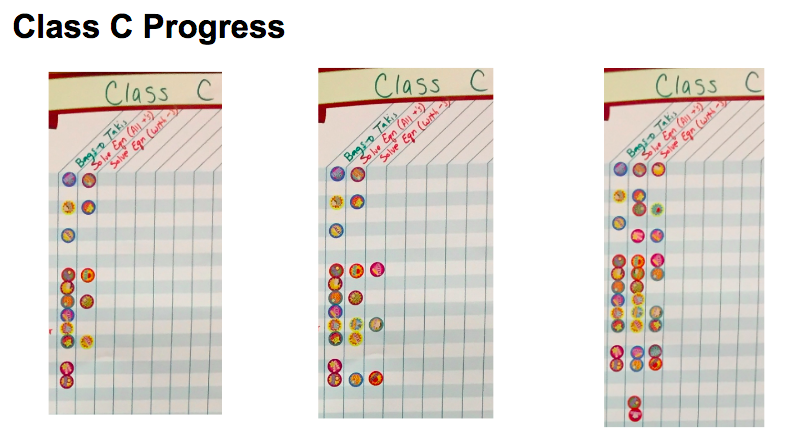

For framing, this past week was one of the more difficult weeks of the school year. A 1st period class was nearly empty one day, one third of another class was consistently late to each day this week, and larger relationship issues between students and between individuals and myself seemed to escalate to more than the normal level.

As a teacher, it is easy to get angry at students. They are late, they are playing, they are misbehaving, and they don’t seem to want to give any respect to me or the other students in the class that are on-time and prepared, ready to learn. I tried all the stages of “pre-anger” as I’ll call it:

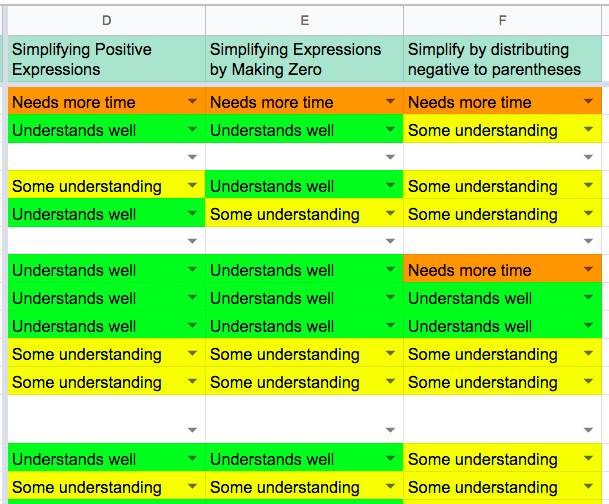

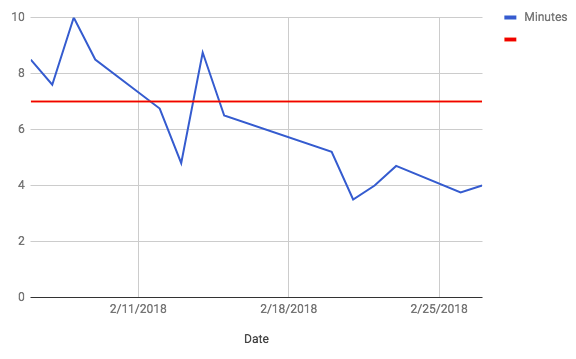

These are my go-to moves, but they just weren’t really addressing the root cause of why these students consistently were having trouble following these expectations. Sure, kids had bad days and needed to check-in about big things happening in their life, but it was clear that the problem was larger than that. It was a good chunk of students in a good chunk of my classes. I’m not a fan of blaming the kids or writing them off as “lazy” or “unmotivated” or even using the crazy things that are going on in their life as an excuse. Instead, I looked inward at the ways in which I set clear expectations in my classroom and communicated my needs with students.

To help frame my thinking, I reflected on some work I studied from David Bradford, a researcher and professor in the business school at Stanford University. Bradford talks about the deep need for clear feedback on behaviors.

“All feedback is positive if it is regarding behavior because we can change our behavior.” (Bradford, 2017).

Bradford writes about the interpersonal cycle in which between two people there are actually three sets of realities. First, the reality of person A, who has their own needs and personal motivations; second, the behavior by person A which is a shared reality between the two people; and third, the reality of person B who receives, interprets, and responds to the action. It is important here to note that the intent of person A can often have a different effect what was intended. Without direct and clear communication and feedback person B is left guessing.

“When we don’t know why the other acts the way they do, we start to guess. This is a natural tendency because we want to have some sense of how the other person might act. We believe that if we understand motivation that it will reduce future uncertainty. (Bradford, 2017).

Based on these thoughts, I’ve been thinking about the ways in which I present myself as person A. In teaching, I have my motives of encouraging all students to learn English (I teach emerging multi-lingual students) and math. I have the needs of sleep and more time, often worn from meetings and other responsibilities held as a teacher-leader. And, I have the situations of tardy students, students talking over other students, and the larger issues of support I face each day in my classroom.

In my mind, I am being reasonable, and it’s the students that are unreasonable. But, Bradford’s work makes me question whether I am actually clear with students. Are my motives clear? Do students understand my expectations? Do they understand why those expectations are important to me, to them, or to the learning process? Are students left to guess what is expected from them or how I will respond?

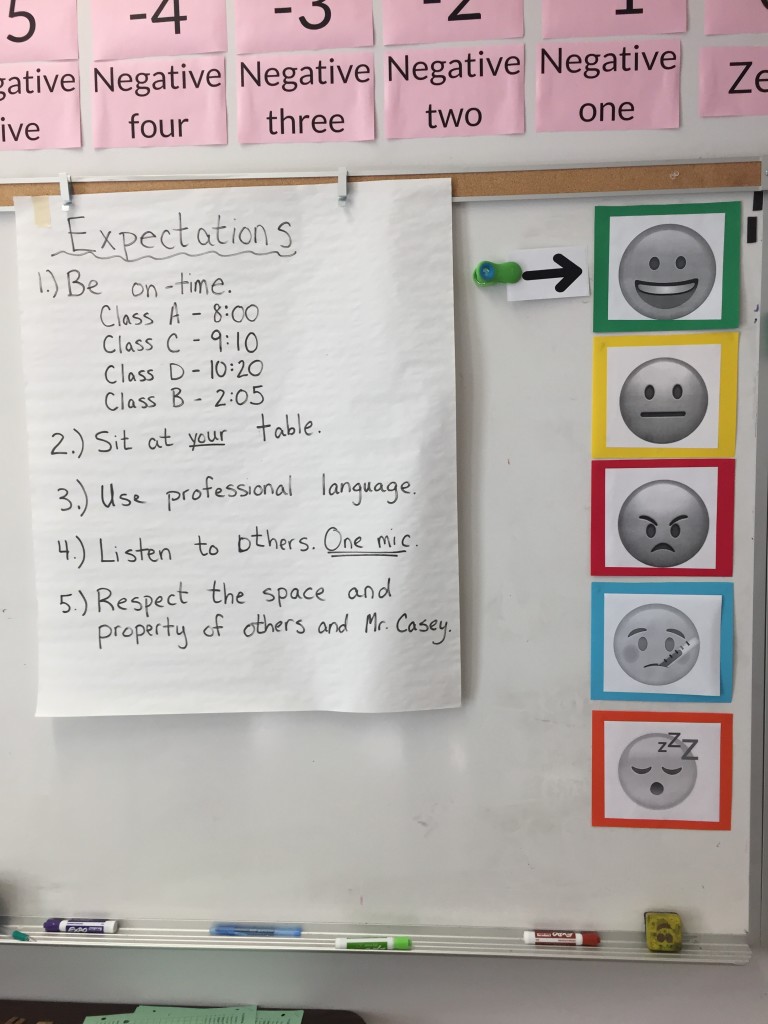

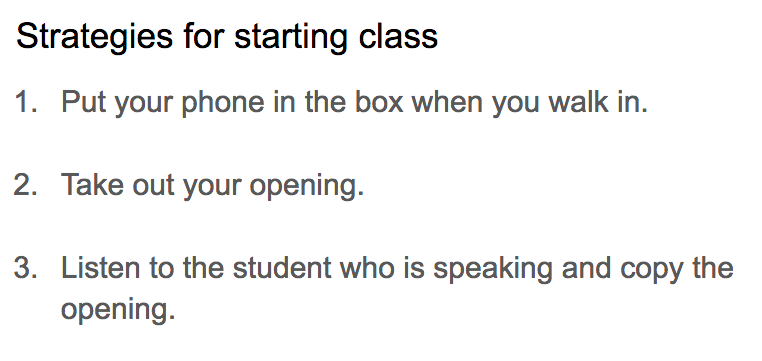

I reflected on the things that I wanted to see more consistently in my class and focused on the positive things I was looking for, avoiding the negatives. For example, instead of saying “don’t throw things”, I wrote “respect the space and property of others”. These were the five expectations I created:

- Be on time.

- Sit at your table.

- Use professional language.

- Listen to others. One mic.

- Respect the space and property of others and Mr. Casey.

Finally, I thought about the ways in which I exert my pre-anger strategies. As a teacher, I have become skilled at remaining calm even though I am severely frustrated. Are the students aware that I am feeling frustrated as I go through those steps? Are they aware that I am getting more frustrated by the moment and their behavior is contributing to the frustration? How can I be more clear about how I am feeling before I reach step 4 or worse? I decided to make it as clear as possible.

Along with my expectations, I plan to post a “mood meter” in the front for all students to see. My hope is that if students have the information they will be able to make better decisions and lessen the need for pre-anger steps one, two or three.

“Feedback is information that gives the recipient options. What they do with it is their choice. They might accept it now or there might be other things they work on. People will change when they are ready to change – not when you are ready for them to change!” (Bradford, 2017).

I’ll try it out starting Tuesday when we are back to school. Wish me luck and feel free to share other expectations/ strategies you use to make things clear for students. Teaching is a process and reflection is key. We can’t make February less cold or less dark, but we can be clear in what we expect from students.

My challenge for others is to think about the interpersonal cycle in your own life with friends, family members, co-workers, or students. How can you be more clear about your own needs and motives in order to more meaningfully connect, inspire, and influence those around you?

Reference:

Bradford, D. (2017). Effective feedback and the developmental process.